By 8 Comments

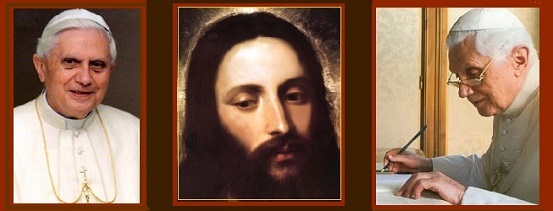

Christians sense there is something radically wrong in trying to put Christ into strange molds, where long-held Christian beliefs about Christ are attacked from all sides. As Benedict stated in his Dunwoodie address to seminarians, to see Christ’s face ” … is a discovery of the One who never fails us; the One whom we can always trust…”

The past century was characterized by ideologies about human nature and society, some of which are now collecting in the dustbins of history. Even in Christian circles, there were attempts to recast Christ as someone reflecting the scholarship, ideology, or mood of the times. Perhaps, this arose out of a kind of boredom with traditional depictions of Christ, perhaps from pride, or just plain delusion. In a work by Romano Guardini, entitled The Humanity of Christ: Contributions to a Psychology of Jesus (1963), Guardini stated:

Our minds, dulled by everything said and written on the subject, can no longer comprehend the passion with which for centuries the early Christians fought out the issues of Christology. 1Guardini saw that Christological distortions would be an especial problem in his times, an attempt to revolutionize our understanding of Christ, a kind of myth-making in keeping with the ideologies at hand. Some post-Enlightenment, Christological illusions depict Jesus as a social prophet, Jewish rabbi, movement founder, healer, revolutionary, meek friend, psychotherapist, not to mention the pre- and post- Easter Jesus, among many others. One particularly harmful depiction was the one commonly known as the “Jesus of History.” Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI made it his special mission to be a mythbuster here—to engage in a determined deconstruction of this particular false depiction of Christ.

The “Jesus of History“

“Jesus of history” portraits are presented as factual—a product of the historical-critical method of biblical exegesis—which arose in the context of increasing archaeological and scientific discoveries in the late 18th and 19th centuries. They emphasized the historically verifiable, the reasonable, in contrast with the Jesus of living tradition, the “Jesus of faith”—the latter seen as imbued with pious and comforting accretions, but with little basis in historical fact. Some early researchers in the quest for the “Jesus of history” were: Romano Guardini, The Humanity of Christ: Contributions to a Psychology of Jesus(1885-1968), whose Deism led him to reject the reality of miracles; David Friedrich Strauss (1808-1874), who asserted that the supernatural elements of the Gospels could be treated as myth; and Ernest Renan (1823-1892), who asserted that the biography of Jesus ought to be open to historical investigation just as is the biography of any other man.In Jesus of Nazareth (2007), Benedict prefaces his critique of the historical critical method by acknowledging that it is a useful first step, which “remains an indispensable dimension of exegetical work” because “it is of the very essence of biblical faith to be about real historical-critical events.” 2 In fact, the encyclicals Providentissimus Deus (1893), Divino Afflante Spiritu (1943), and Pontifical Biblical Commission documents had encouraged historical research. Without recognizing Christianity’s historical dimension, Benedict says, there is a danger of gnosticism, stressing personal enlightenment alone. Christianity, Benedict stresses, lies on the factum historicum, not symbolic ciphers, or concepts alone:

“Et incarnatus est”—When we say these words, we acknowledge God’s actual entry into real history. 3That having been said, Benedict goes on to critique the views of ”Jesus as history” scholars, such as: Adolf von Harnack (1851-1930), Martin Dibelius (1883-1947), and Rudolf Bultmann (1884-1976). They viewed the probable and measurable as solely of value, relegating miracles to the realm of doubt or myth. 4 Benedict explains that even outstanding biblical scholars, such as Schnackenberg, can end up constrained by its methods. 5 The historical-critical method fueled hermeneutical suspicion about everything in some quarters, and sparked ‘‘anti-Christologies,” leaving genuine seekers for Christ submerged in endless scholarly conflicts and questioning, wondering if the Gospels themselves were genuine. The shifting hypotheses of exegetes, as Avery Dulles noted, led to neglect of tradition, and historical research became “the highest doctrinal authority of the Church.” 6

Some of the damaging legacy which undermined traditional Christological portraits, can be seen in this website account:

Jesus is not the only-begotten Son of God sent to earth to die for our sins. Rather, he is one of us who, as a man, simply had an unusual degree of experiential contact with God. He says remarkably little about himself. Having found freedom himself, his only goal is to help us find it. 7Another “Jesus of History” came from Father John Meier, professor of New Testament at Washington, D.C.’s Catholic University of America, who declared in A Marginal Jew (1991), that —“on painstaking deductions from the New Testament” and “other knowledge about the Graeco-Roman cultures in which Jesus and his followers moved”—that Jesus was probably married, had four brothers and sisters (not cousins), and that he was born in Nazareth not Bethlehem. 8

Most Christological portraits—especially those à la Bultmann—deconstruct Jesus to be an ordinary, first century, Jewish rabbi, about whom little can be said, except that Jesus is not the “person” the reader thought he was, that is, the Son of God, as proclaimed in Scripture and tradition for millennia. After perpetual deconstruction, Benedict notes, scholars often are then obliged to resort to novel reconstructions in order to explain how everything came about, their “sheer fantasy” based on their philosophical proclivities. 9

Obfuscating theologians

The historical-critical method thus becomes a meta-method, a broad funnel through which continual Christological deconstruction and reconstruction flows, blind to its own philosophical assumptions, breaking the memoria ecclesiae, ensnaring the innocent. Benedict interprets the passage: “Whoever causes one of these little ones who believe in me to sin, it would be better for him if a great millstone were hung around his neck and he were thrown into the sea” (Mark. 9:42), as not only referring to sexual abuse victims, but also to victims of obfuscating theologians and exegetes, who deconstruct and obscure Christ’s face. 10 Similarly, Benedict has quoted Joseph Gnilka’s view that “The devil presents himself as a theologian,” especially one involved in biblical exegesis. 11The “crisis” Benedict referred to is that of conflicting historical-critical theories, which instead of unveiling the traditional Jesus of the Johannine, Synoptic, and Pauline Christologies, have created biblical cataracts for hapless seekers. Benedict underlines the method’s unreasonableness in highlighting the “word” (and its endless interpretations) as opposed to the unique “event” of endlessly exposing “discontinuities” of text; and insisting that “simple” accounts are original and believable, while “complex” accounts are later Hellenic, mythic impositions on earlier Semitic paradigms—the paradigms and myths selected according to the writer’s taste. The historical-critical method’s major flaw is that it is anti-historical in the sense that it is not open to revelation of a unique historic event, of God entering time, the basis of any Christology.

Deconstructing the hermeneutic of suspicion

Benedict sees the philosophical roots of historical-criticism (especially in Bultmann) in the Kantian belief that the noumenon—the thing-in-itself—cannot be known, and only the methods of natural science can recreate Christ. This constitutes an unreasonably narrowed focus, an ostracism of metaphysics, an ontological phobia. In a skillful volte-face, Benedict applies a similar hermeneutic of suspicion to the methods of the scholars themselves, saying: “What we need might be called a criticism of criticism.” 12 Praising a doctoral dissertation by Reiner Blank, entitled: “Analysis and Criticism of the Form-Critical Works of Martin Dibelius and Rudolph Bultmann,” as a “fine example of a self-critique of the historical-critical method,” he enlists Heisenberg’s “Uncertainty Principle” in his attack:Now, if the natural science model is to be followed without hesitation, then the importance of the Heisenberg principle should be applied to the historical-critical method as well. Heisenberg has shown that the outcome of a given experiment is heavily influenced by the point of view of the observer. 13Thus, in the Heisenbergian spirit, Benedict critiques the “Jesus of history” for its uncertainties! He does so under two main headings in Jesus of Nazareth. First, he says that the historico-critical method is restricted to leaving the biblical word in the past, which contradicts the Gospel’s claim that Jesus is the eternal Logos who is not confined to time. The Scriptures reach out to all, beyond the past, the moment “a voice greater than man’s echoes in Scripture’s human words.” 14 Jesus’ revelation of God “really did explode all existing categories, and could only be understood in the light of the mystery of God.” The words and events of Christ’s “life” transcend time and “one must look at them,” Benedict says, “in light of the total movement of history, and in light of history’s central event, Jesus Christ.” 15 True, Christology requires openness to divine revelation as a fact in itself, even if one takes into account Heisenberg’s understanding of the human predisposition to perceive this reality in a manner suited to the knower.

Benedict describes the second major limitation of “Jesus of History” portraits as presupposing “the uniformity of the context within which the events of history unfold,” therefore treating ”biblical words it investigates as human words.” 16 This eradicates Jesus’ supra-human claim that he came to do his Father’s will. Highlighting this in his essay on Guardini’s book, The Lord, Benedict says:

The figure and mission of Jesus are “forever beyond the reach of history’s most powerful ray” because “their ultimate explanations are to be found only in that impenetrable territory which he calls ‘my Father’s will.’” 17Benedict goes on to say,”One simply cannot strip ’the Wholly Other,’ the mysterious, the divine, from this Individual. Without this element the very Person of Jesus himself dissolves.” 18 When, as is recounted in Jesus of Nazareth, the rabbinical scholar, Jacob Neusser, reads the Gospels with an open mind, he concludes that the dramatic, universal, plainly understood message of the New Testament is Christ himself, who is the Son of God, and who invites us into this heavenly family. Benedict, implicitly asks, if a Jewish scholar can see it, why can’t Christian exegetes?

Jesus understands himself as the Torah—the word of God in person … Harnack, and the liberal exegetes, went wrong in thinking that the Son, Christ, is not really part of the Gospel about Jesus … The truth is that he is always at the center of it … The vehicle of universalization is the new family whose only admission requirement is communion with Jesus, communion in God’s will. 19So radical is the claim that “Jesus understands himself as the Torah“—the center and living unity of the Old and New Testaments—that the Jewish scholar is so overwhelmed that he can hardly absorb it, recognizing its extraordinary claim as one that Buddha, Mohammed, or other religious leaders never made. Benedict uses the rabbi’s fresh observations to perform myth-busting on historical deconstruction, reminding us that “humble submission to the word of the sources” dynamically unveils Jesus—and “he who sees Christ, truly sees the Father; in the visible is seen the invisible, the invisible one.” 20

The distortions of the “Jesus of History” are now, in fact, becoming “history” for Christ—not Christophobia—always arising in eloquent simplicity out of the hazy distortions, and rusting ideologies, of past and current deceptions. Christians sense there is something radically wrong in trying to put Christ into strange molds, where long-held Christian beliefs about Christ are attacked from all sides. As Benedict stated in his Dunwoodie address to seminarians, to see Christ’s face ” … is a discovery of the One who never fails us; the One whom we can always trust. In seeking truth, we come to live by belief because, ultimately, truth is a person: Jesus Christ.” 21 Re-awakening Christians from their historical-critical hypnosis, in a very clear way, has relegated the “Jesus of History” to the realm of mummified theories, unveiling Christ, who always invites our trust throughout the ages. This relentless and successful myth-busting of a “learned” but false depiction of Christ will be one of Benedict’s most profound and lasting legacies, now, and in the time to come.

- Romano Guardini, The Humanity of Christ: Contributions to a Psychology of Jesus. 3rd Edition. (NY: Random House, 1964). Originally published in German as Die Menschliche Wirklichkeit Des Herrn. in 1958 by Werkbund-Verlag, Wurzburg.

http://www.ewtn.com/library/CHRIST/HUMAN.TXT (Retrieved 8/2/2009). ↩ - Pope Benedict XVI, Jesus of Nazareth, (London: Bloomsbury, 2007), xvi. ↩

- Ibid., xv. ↩

- Ibid., xi-xix: 34-38. Similar points were made by Ratzinger in a previous lecture and publication. Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, “Biblical Interpretation in Crisis: On the Question of the Foundations and Approaches of Exegesis Today,” in R. J. Neuhaus, ed., Biblical Interpretation in Crisis (Grand Rapids : William B. Eerdmans, 1989). Originally delivered as an Erasmus Lecture at St. Peter’s Lutheran Church in New York City on 27 January 1988. Also available at: http://www.catholicculture.org/library/view.cfm?recnum=5989 Retrieved 3/21/2013). ↩

- Pope Benedict XVI, Jesus of Nazareth, (London: Bloomsbury, 2007), xiii. ↩

- Avery Cardinal Dulles SJ, “Benedict XVI: Interpreter of Vatican II,” Laurence McGinley Lecture, Fordham University, October 25, 2005. Article also appears as: Avery Cardinal Dulles SJ, “From Ratzinger to Benedict,” First Things, October 2006. Quotation taken from website containing this article: http://www.firstthings.com/article.php3?id_article=86 ↩

- http://www.circleofa.org/articles/PortraitOfJesus.php (Retrieved 3/4/2012). ↩

- http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9D0CE4DA133FF930A15751C1A967958260(2/2/2011). ↩

- Joseph Ratzinger, God and the World, (San Fransisco: Ignatius press, 2000), p 227. ↩

- Joseph Ratzinger, The Nature and Mission of Theology, (San Fransisco: Ignatius, 1993) p.67-68. ↩

- Pope Benedict XVI, Jesus of Nazareth, (London: Bloomsbury, 2007), p.34. ↩

- Erasmus Lecture: http://www.catholicculture.org/library/view.cfm?recnum=5989 . ↩

- Erasmus Lecture: http://www.catholicculture.org/library/view.cfm?recnum=5989 .

Benedict makes the same point in an article entitled “On the 100th anniversary of the Pontifical Biblical Commission, Relationship Between Magisterium and Exegetes,” L’Osservatore Romano, Weekly Edition in English, July 23, 2003, p. 8, where Benedict says: “… we have also learned something new about the methods and limits of historical knowledge. Werner Heisenberg verified, in the area of the natural sciences, with his “Unsicherheitsrelation,” that our knowing never reflects only what is objective, but is always determined by the participation of the subject as well, by the perspective in which the questions are posed and by the capacity of perception.” ↩ - Pope Benedict XVI, Jesus of Nazareth, (London: Bloomsbury, 2007), p xvi. ↩

- Erasmus Lecture, http://www.catholicculture.org/library/view.cfm?recnum=5989 . ↩

- Pope Benedict XVI, Jesus of Nazareth, (London: Bloomsbury, 2007), pxvii. ↩

- Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, “Guardini on Christ in our century.” Retrieved from: https://www.ewtn.com/library/homelibr/thelord.txt (4/10/2014). ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Pope Benedict XVI, Jesus of Nazareth, (London: Bloomsbury, 2007), pp. 110, 116. ↩

- Josph Ratzinger,”Jesus Christ Today,” Communio, Vol 17, 1990, p. 80. ↩

- http://www.ssmi-us.org/downloads/ssmi-vocation-dunwoodie.pdf ↩

No comments:

Post a Comment